Exchange Rate Regimes and Monetary Policy in a Global Inflationary Environment

The recent episode of global inflation is a reminder that no country lives in isolation. Like other external economic shocks,inflationary pressure too could pass through to domestic economies. In June,inflation in the United States climbed to a 40-year high,rising 9.1% over the last 12 months,as measured by consumer price index (CPI). In the same period,the euro zone inflation continued to set historical record at 8.6% for the entire bloc,as measured by harmonized CPI. Meanwhile in China,the signals were more mixed,with CPI rising 2.5% to a 23-month high,despite producer price index (PPI) sets a 15-month low,largely due to the pandemic disruptions.

Inflationary pressure among large economies creates uncertainty for the rest of the world,as cross-border trade linkage and capital flow have important domestic implications for other countries’ currency and monetary policies. This uncharted territory of global inflation calls on central banks around the world to take a differentiated and flexible approach to navigating inflation under different exchange rate regimes and domestic constraints.

Exchange rate regime: One size does not fit all

Evolution of theoretical foundation for optimal exchange rate

With the collapse of Bretton Woods system in the early 1970s,International Monetary Fund (IMF) members have been free to adopt any exchange rate regime that suits its domestic economic objectives. However,the optimal exchange rate arrangement for a country remains an open question.

Generations of international economists have hypothesized and expounded arguments for various forms of currency arrangements. Many previously settled intellectual debates have been reexamined,as new theories and evidence emerge. It is helpful to revisit some of the most prominent arguments,as they form the theoretical foundation that has influenced central bank actions over the past decades. And some remain influential today in guiding central banks’ response to global inflationary pressure.

The free floating exchange rate regime that most advanced economies follow could trace its theoretic roots to the mid-20th century. When an economy faces country-specific shocks that call for relative price adjustment,there are broadly two ways for the economy to adapt – either domestic prices need to change,or the exchange rate to adjust. Given that domestic prices can be sticky,exchange rate adjustment is much easier. Milton Friedman (1953) famously drew the analogy between floating exchange rate and daylight savings time.

“The argument for a flexible exchange rate is,strange to say,very nearly identical with the argument for daylight savings time. Isn't it absurd to change the clock in summer when exactly the same result could be achieved by having each individual change his habits? All that is required is that everyone decides to come to his office an hour earlier,have lunch an hour earlier,etc. But obviously it is much simpler to change the clock that guides all than to have each individual separately change his pattern of reaction to the clock,even though all want to do so. The situation is exactly the same in the exchange market.”

On the other extreme of exchange rate regime spectrum,a currency union,as a strict form of fixed exchange rate,emerged in the 1960s. While currency policy is often discussed as a national policy,Robert Mundell (1961) expounded that exchange rate does not have to be bounded by national borders. The theory for optimum currency areas (OCA) was credited as the intellectual foundation for the euro,though whether the euro zone countries all meet the OCA criteria remain contested. In the current global inflationary environment,the benefits and challenges of currency unions are being observed and tested across the euro zone,West African CFA franc zone,Central African CFA franc zone,and other smaller currency unions.

While many intermediate exchange rate regimes exist,Barry Eichengreen (1994) offered the “corners hypothesis” that the only feasible options for exchange rate arrangements in the long term would be either free floating or a monetary union. Eichengreen postulated that countries would be forced to choose from the two corners of exchange rate regime spectrum – that is,a country can either free float its currency without intervention,or establish firm commitment to fixed exchange rate – because a high degree of capital mobility would make any intermediate exchange rate regime unstable and crisis-prone. Under the hypothesis,sustaining an adjustable peg,like the Bretton Woods system and the European Monetary System (EMS),could not be successful.

As the benefits and costs of floating versus fixed remain contested,John Williamson (2001) proposed a middle-of-road option for emerging economies in East Asia. The “basket,band and crawl (BBC)” proposal includes features of several immediate regimes – It advocates pegging to a basket of currencies,especially for countries with diversified trade; it suggests a wide band in which exchange rate can fluctuate without unnecessary interventions by central banks; it allows for a crawling adjustment to neutralize differential inflation and reflect real changes in the economy.

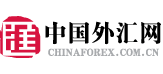

Complexity in detecting de facto exchange rate regime

In addition to the evolution of theories,there is additional complexity to determine the de facto exchange rate regime that a country practices. Countries sometimes deviate from their officially stated exchange rate regime. And even when countries do follow their stated exchange rate regime,in the case of a basket peg,transparency of the basket composition could be low,increasing the complexity to detect the de facto currency policy in practice.

Counties might periodically change the exchange rate regime it follows. An IMF study (Das 2019) reviewed several distinct phases of the exchange rate policy that China has practiced since its departure from a fixed exchange rate regime in 2005. In the subsequent decade,China mostly maintained a stable exchange rate against the US dollar. Between 2015 and 2016,pressured by capital outflow,China attempted to intervene in the foreign exchange market to cushion the depreciation of the renminbi. Since 2017,renminbi remained largely stable against a basket of currencies.

When China first announced its move into a managed floating regime in 2005,it did not specify the basket composition. In 2015,the People’s Bank of China (PBC),for the first time,officially published the composition of a basket of 13 reference currencies,where the US dollar,euro,and Japanese yen account for 62% of the CFETS RMB index. In 2016,China broadened the basket to include 24 reference currencies,reducing the combined weight of the US dollar,euro,and Japanese yen to 50%.

Given the complexity in determining a country’s de facto exchange rate regime,as well as the periodical deviation from a country’s stated currency policy,it could be difficult for other countries to formulate policy responses to external shocks. For example,pre-pandemic,the domestic pressure in the United States to label China a currency manipulator missed the mark. China’s intervention in the foreign exchange market was in fact in the opposite direction of the accusation – renminbi was likely to depreciate if China did not intervene between 2015 and 2017. The brief period when the US Treasury Department formally named China a currency manipulator in 2019 was widely criticized,as it contradicts to Treasury Department’s own analyses. It is worth noting that the US Treasury Department criteria for currency manipulation also diverge from international standards.

Exchange rates regimes in inflationary environment: Evolving perspectives

As the availability of time series data grows and other sources of empirical evidence come to light,the relationships between exchange rate regimes and inflation are increasingly an area where new insights emerge.

Earlier study by the IMF (Ghosh et al. 1997) found strong link between fixed exchange rates and low inflation. It attributed the results to discipline and confidence effects,where a fixed exchange rate signals a stronger political commitment and induces greater demand for the domestic currency. Specifically,money supply grows at a slower rate in countries with fixed exchange rate,because the discipline effect suggests political costs could be too high to abandon a peg. At a given rate of growth in money supply,countries with fixed exchange rate could induce greater demand for domestic money via enhanced confidence in investments.

The perspectives on the optimal choice of exchange rate regime continue to evolve and have become more nuanced,especially for developing and emerging economies. While evidence remains strong to support the association of fixed exchange rate regimes and inflation performance,the key to ensure inflation benefits is to match your deeds with words – a de facto peg without a de jure commitment does not deliver the same benefits of anchoring inflation expectation (Ghosh and Ostry 2009).

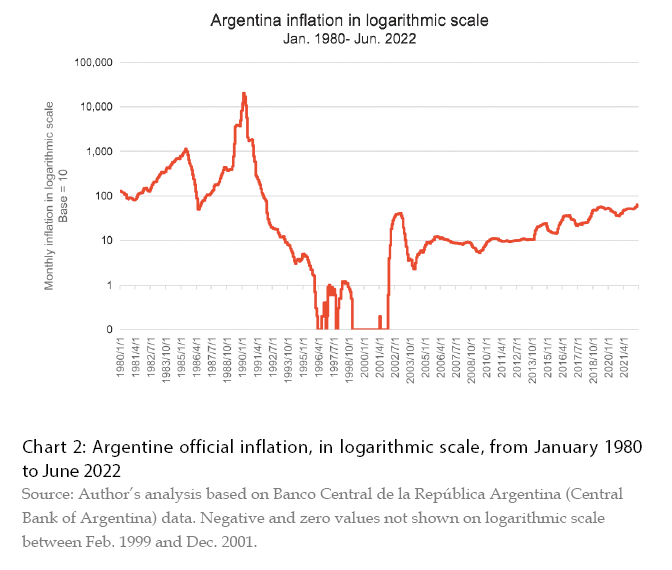

Exchange rate regime alone provides no guarantee of low inflation,as the credibility of a central bank and the government is a key asset to ensure currency and monetary policy effectiveness. For instance,over the past decades the Central Bank of Argentina (BCRA) has experimented with various exchange rate arrangements,from a currency board (a form of fixed exchange rate) to free floating,and many intermediate regimes in between (including a crawling peg,a managed float). The results on inflation,however,have been meager. Between 1991 and 2002,when a currency board was in place,Argentina experienced some of the worst episodes of hyperinflation. Nevertheless,Argentina’s failure does not necessarily invalidate the potential inflation benefits of a fixed exchange rate regime. In fact,Argentina’s currency board lacks many features of an orthodox currency board and thus is only a fixed rate regime in name. It violated full convertibility by extending preferential rates for exports. It effectively lent to the government and acted as a lender of last resort to commercial banks. It was not sufficiently backed by dollar reserves.

Insulation from imported inflation for the country of international currency

The late