Potential Growth Underestimated under Conventional Framework

Author: ZHANG Wenlang, ZHOU Peng and HUANG Yadong

As China is in the second half of the financial cycle, economic growth has slowed, and market forecasts for China’s economic growth have been revised down several times. The evolution of China's potential growth, i.e., the economy’s sustainable rate of growth, has drawn attention. We believe the conventional framework under which inflation is used to measure the sustainability of economic growth tends to overestimate the potential growth in the first half of the financial cycle but underestimate it in the second half. That is to say, China's potential growth rate could be higher than the estimates made under the conventional framework.

Breaking free from conventional thinking to estimate potential output

Potential output should be sustainable output that makes full use of various inputs of factors of production, which can also be interpreted as the desirable level of output. In fact, potential output is not observable, and it is estimated on the basis of models and assumptions. This implies that different models or assumptions could yield different estimations.

Under the conventional framework, the main indicator used to measure the sustainability of economic growth is inflation. Inflation rises when actual output is higher than potential output, and vice versa. A commonly used model is the Phillips curve, which assumes a close relationship between output and inflation. The difference between actual output and potential output is commonly referred to as the output gap. In general, the output gap rarely equals zero because the economy is rarely in equilibrium. However, in a special case, namely in the Real Business Cycle model, actual output always equals potential output (output gap is zero), which illustrates an extreme case.

However, the subprime mortgage crisis shows that inflation is not the sole indicator for the sustainability of output, and it is not even the most important indicator in an era with highly developed financial markets. The subprime mortgage crisis of 2008 fully exposed the flaws of the conventional framework. Given the moderate inflation and swift growth during the Great Moderation, it was once widely believed that the growth in major Western economies during that period would be sustainable, leading to a sense of complacency among Western monetary policy makers at some point. However, the subprime crisis showed that growth during the Great Moderation was unsustainable, suggesting inflation was not the sole indicator for the sustainability of output.

At the aggregate level, even if inflation is moderate, output can still be unsustainable in the case of rising financial imbalances. A financial boom may temporarily boost output (e.g., increased investment by financial accelerators) and push down inflation, but the output brought by the financial boom is not necessarily sustainable. Structurally, a financial boom may lead to misallocations of resources across industries. For example, the real estate industry, which is very sensitive to credit, could expand rapidly, while industries that lack collaterals could be squeezed out. The misallocations in resources would eventually be corrected, either passively (e.g., through a crisis) or actively (through policy guidance).

Therefore, the sustainability of output depends on both inflation and financial indicators. Accordingly, we need to take into account potential imbalances in both the real economy (e.g., inflation) and the financial sector (e.g., asset prices) when calculating potential output (the sustainable, desirable level of output). Such a view is fully illustrated in a research by Bank of International Settlements researchersin 2017. 1

In fact, the difference between the two perspectives lies in the perception of money, i.e., how to view the role of money. As we all know, classical economics separates money from the real economy. Classical economists believe that money is just a “veil” that only affects prices but not the real economy. By contrast, Keynes believed that money was an intrinsic part of the capitalist market economy. Money influences people's economic decision making, thereby affecting allocative efficiency, and accordingly the real economy.

Such a difference is essentially related to the debate between neutrality and non-neutrality of money. The neutrality of money holds that prices are flexible and money only affects prices and not the real economy (output). New classical economics holds that money is non-neutral in the short run and it affects output. However, money is neutral in the long run and does not affect output. Today's New-Keynesian economics is closer to new classical economics by nature, as it believes that money is non-neutral in the short run but neutral in the long run.

If we delve deeper, such a difference involves the understanding of the function of money and banks. The neutrality of money emphasizes the function of money as a medium of exchange, as reflected by the equation of exchange. By contrast, the non-neutrality of money emphasizes the function of money as a store of value, and the idea is that money is not only a means of payment but also an asset. Keynes introduced the so-called liquidity preference theory on this basis, and in extreme cases, the liquidity trap could arise. Regarding the functions of banks, mainstream economics believes that the main function of banks is to “distribute” money as intermediaries. However, Keynesian economics believes that banks not only “distribute” money, but also “create” money and purchasing power.

Structurally, money affects the economic structure via the sequence and amount of money supply. Those who get the money first could see actual purchasing power increase as prices have not yet risen, while the actual purchasing power of those who get the money later could be weaker as prices have started to rise. Therefore, money does influence the economic structure. In addition, money supply is not evenly distributed among different parts of the economy, with different sectors and entities receiving different amounts of money. The money supply could also affect the economic structure over the long run.

In his classic work The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time published in 1944, Karl Polanyi, a well-known thinker of the 20th century pointed out that “what the businessman, the organized worker, the housewife pondered, what the famer who was planning his crop, the parents who were weighing their children’s chances, the lovers who were waiting to get married, revolved in their minds when considering the favor of the times, was more directly determined by the monetary policy of the central bank than by any other single factor" 2 The significance of money is self-evident.

Therefore, we need to estimate potential output and growth by incorporating information about financial cycles, of which the theoretical basis is the non-neutrality of money. A business cycle spans one to eight years, with GDP (growth) and CPI (inflation) being the representative indicators. By contrast, the formation of a financial cycle is caused by the mutually reinforcing housing prices and credit. A financial cycle spans 15–20 years, with home prices and credit being the main indicators.

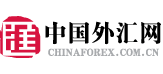

Our analysis based on the framework adopted by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) shows that financial cycles diverged in China and the US (Figure 1). The first half of the previous financial cycle in the US lasted from the 1990s to around 2008, and the second half extended from about 2008 to 2013. The US is currently in the upswing of a new financial cycle. As the US strengthened financial regulation after 2008, the upward slope of the current financial cycle in the US was milder than before 2008.

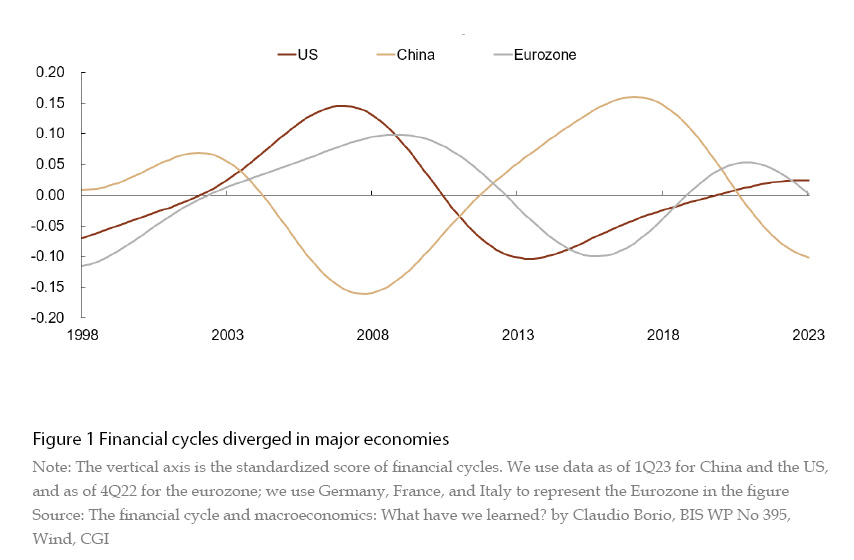

Financial cycles magnify fluctuations in business cycles. According to BIS, the economy tends to post stronger performance during upswings of financial cycles than during downturns (Figure 2). This could also lead people to overestimate the potential growth in the first half of the financial cycle and underestimate it in the second half.

Why conventional frameworks tend to overestimate potential output in the first half of the financial cycle According to the Phillips curve, potential output = actual output -θ(real inflation - long-term inflation). The parameter θ represents the elasticity of the output gap to inflation gap. According to this equation, assuming other variables are held constant, rising actual output would drive up potential output, while a fall in actual inflation also pushes up potential output.

In the first half of the financial cycle, the financial boom drives up leverage. Most sectors can easily borrow money, and they have strong incentives to borrow. Due to information asymmetry and other reasons, the positive financial accelerator effect reduces financial constraints, and increases the pro-cyclicality of the financial sector, boosting demand and output across the board. Meanwhile, more funds flow to assets (especially real estate) in the first half of the financial cycle, and demand for assets is reflected in rising asset prices rather than rising inflation. In other words, money supply increased rapidly, but it was not reflected in inflation. As a result, potential output could easily be overestimated. This view has been elaborated by Borio, Claudio, Piti Disyatat, and Mikael Juselius (2017).

On the supply side, accelerated expansion of non-productive sectors (e.g., finance and real estate) exacerbates misallocations in resources, indicating the expansion of non-productive se