Implications of the Funding Crunch

In June 2013,there was a rare “money shortage” in China’s financial market: the repo rate reached a record high of 30%,bond issues failed and yields rose sharply. Massive fund redemptions followed,straining the market infrastructure. Some institutions defaulted and the stock market plummeted.

Money shortages – dangerous and sometimes surprising in their severity – are not necessarily a thing of the past. Some – though not all – of the contributing factors are still with us today. The fact that various factors were intertwined and appeared together at a sensitive time made this cash crunch one of the most complex events in China's financial history.

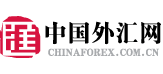

More recently,the US had its own taste of a money shortage. On September 16,2019 the effective federal funds rate,or EFFR,suddenly surged. (The federal funds rate is the interest rate at which depository institutions lend balances at the Federal Reserve to other depository institutions overnight.) The weighted average rate rose from the previous session’s 2.15% to 2.25%. That reached the upper limit of the federal funds target rate (FFTR) range of 2-2.25% and exceeded 3% at its peak. The next day,the EFFR continued to rise,with the weighted average rate reaching 2.3%,again breaking the upper end of the FFTR range and briefly exceeding 4%. (See Chart 1) The repo rate,meanwhile,shot up to a dangerous 10%,a highly unusual level. This was an American funding crunch.

9

9

What might be behind this kind of money market volatility? What are the implications and what remedies are available to policy makers?

Financial disintermediation is one of the main contributors. It is an inevitable stage in the development of a multi-tiered capital market as well as the promotion of financial deepening and interest rate liberalization. The US completed this process in the 1990s and brought about a complete transformation of the financial sector. In recent years,the pace of China's financial disintermediation has been very fast,and this has led to significant changes in the structure of financial assets.

But every coin has two sides. Financial disintermediation can be good,and it is important to make a sober assessment of its possible impact. In a column titled “Financial Disintermediation Alarm” in Caixin Weekly in April 2012,I made an analysis,in which I specifically mentioned that it would “lead to the normalization of liquidity tightness,” and abnormal conditions would occur under certain conditions.

The “money shortage” that occurred in China in June 2013 created lingering fears. But we should not forget that despite the different contributing factors and severity of the problems,money shortages are not uncommon in history.

One can see the present better by looking at the past. What happened in 2011 is another example. The seven-day repo rate peaked at 10% in June of that year and remained at 7% in December. The bill's direct interest rate reached 13% in September. Many of the traditional institutions which used to provide a lot of money to the market were suddenly in need of funds.

Sometimes,at times of great market pressure,some previously sound institutions implode.

What is the explanation for this? The data show that the central bank's liquidity withdrawal was very limited,and its liquidity offsetting ratio was as low as it was in 2009 when the liquidity was generally loose. So,the monetary authorities’ open market operations can be ruled out as the root cause.

In my opinion,the tight policy tone that began in 2011 as well as strengthened macro-prudential supervision and concentrated disclosure of credit risks were contributors to tight liquidity. But the explosion of wealth management products was the main reason. In that year,the circulation of various wealth management products nearly doubled. The balance rose from 5.5 trillion yuan to 9 trillion yuan. Such products have the natural characteristics of credit intermediation,term restructuring and liquidity conversion,as well as the use of some leverage and the exploitation of regulatory gaps. The rapid expansion also sped the movement of capital across the balance sheet,from the supply side as well as the demand side. This naturally increased volatility.

Going back to the end of 2010,there was another period of money shortages. A number of institutions lacked funds and defaulted. This phenomenon continued until the 2011 Spring Festival.

There are earlier examples as well. In 2007,as the stock market soared and drew funds from the banking system,a large amount of money was put into wealth management products that could be used to buy stock in new share offers. This resulted in a spike in short-term interest rates and a situation of “loose macro liquidity and tight micro liquidity.” At that time,financial disintermediation was not obvious,and the balance of wealth management product and trust assets was only 1,336 billion yuan. Although the background factors were different and the financial stresses were limited to a few areas,financial disintermediation began to show up.

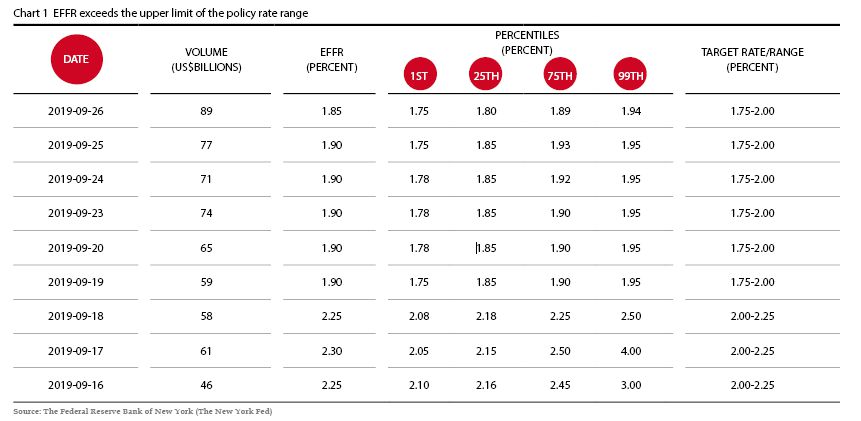

Now let’s look at the situation in June 2013,when repo rates hit the 30% level and bonds were sold off. (See Chart 2)

This was largely a cash crunch. The reasons included gambling on the balance between the demand and supply of capital and regulatory storms that changed the familiar rules of the game. However,there is no doubt that financial disintermediation,wealth management products and shadow banking played a part. Most of the discussions about high leverage ratios,inter-bank business expansion and off-balance sheet business were related to this.

However,from the rare direct linkage between the money,bond and stock markets,it is clear this was actually more than a “money shortage.” It was in fact a financial shock caused by more complex factors that had a knock-on effect - what I call the “June shock.”

Imagine this: if the funding situation in June 2013 had been more normal,would the stock market have slid on the Fed's desire to quit easing combined with the continued weakness in China's economic data and the potential financial risks? And add to that the insistence on not introducing stimulus measures at the time – would that have been enough to trigger a stock sell-off? Probably,yes! So,the “June storm” was not only a “money shortage.” The “money shortage” was just the visible part of the phenomenon.

It is not hard to see that this round of financial turmoil was actually a global phenomenon and not unique to China. When then-US Federal Reserve chief Ben Bernanke testified to Congress in May of 2013,he gave the first hint of winding down quantitative easing,causing global stock and bond markets to fall – and that was especially pronounced in Japan. Chinese stocks also opened lower,with losses magnified after May 31. At a June 19 press conference,Bernanke made a surprise reference to tapering the existing super loose monetary policy and ultimately ending it. Global equity markets plunged again,bond yields surged and the dollar strengthened.

Market expectations were also hit by weak fundamentals in the Chinese economy,rising debt burdens and emerging potential financial risks. Despite disappointing economic data in the first quarter of 2013,the market had expected the second quarter to improve. April data were another negative surprise and the May data blew away any remaining confidence. Doubts about the authenticity of the import and export figures added to the uncertainty.

At the same time,there were signs that China was not ready for a new stimulus.

These factors were the direct cause of the sharp drop in China’s stock market in June of that year and the outflow of foreign capital. The impact was magnified by the shortage of money.

Overall,various factors were intertwined just at that sensitive time. The “June storm” became one of the most complex events in China's financial history. Financial disintermediation is the main cause of a “money shortage.” But the “June storm” was a chain reaction caused by a variety of factors and it was a reminder that in today’s increasingly complex economic and financial world,both market and policy levels require caution,preparation and a careful response. Some people think that the “June storm” was the beginning of China’s financial crisis. Although there were problems,proper reflection can help our understanding and point to the right direction to reduce hidden risks.

We still have a problem with disintermediation,though there are substantial differences between now and then. Now,regulators and financial institutions have been more prepared to prevent another 2013-like money shortage. But the issue is: because of the financial deregulation and liberalization,because of disintermediation,since June 2013,the size of China’s leverage – the shadow-banking system,has increased dramatically,with enormous risky lending practices taking place. In order to work around rules of lending,evade capital and provisioning requirements,some smaller commercial banks exposed themselves to a much wider spectrum of risk. In May 2019,regulators assumed control of Baoshang Bank Co. for one year citing “serious” credit risks,which became China’s first bank seizure since 1998. Baoshang is a small city-commercial lender that obscured its exposure to risky borrowers by tapping into the shadow-banking system. China Construction Bank Corp.,one of the nation’s largest lenders,was brought in to manage Baoshang’s business while it’s under government control. Though the seizure of Baoshang was an isolated incident,it led to a sharp rise in repo rates and borrowing costs for smaller banks and nonbank institutions immediately after the seizure.

The American Funding Crunch

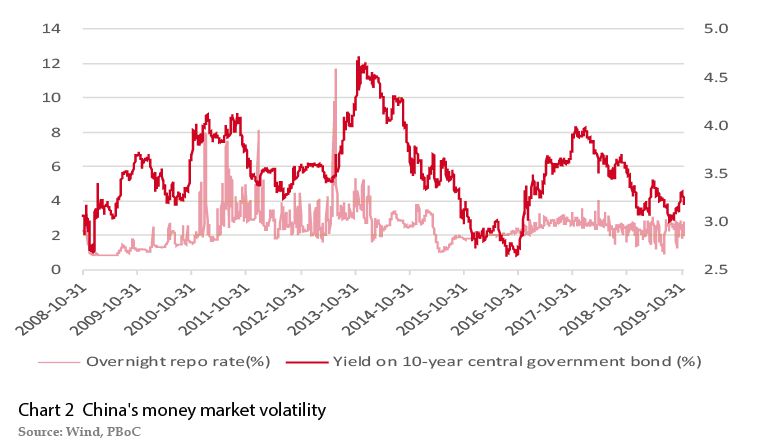

On September 17 of this year,the rate on the overnight general collateral repo in the US jumped to 10%,about four times its normal level. The New York Fed stepped in for the first time since the 2008 financial crisis,releasing $53 billion in overnight financing. Three days of operations followed,raising the amount of overnight funds to $75 billion a day. On September 20,the New York Fed announced that it would roll out $75 billion in overnight funds every day from September 23 until October 10,with three 14-day repurchase agreements of at least $30 billion each. (See Chart 3) In October,the operations continued with an expanded scope.

Markets had fully anticipated the September 18 rate cut by the Federal Open Market Committee,which determines the appropriate stance of US monetary policy. However,money was tight and interest rates surprisingly shot up that week,putting Federal Reserve Board Chair Jerome Powell in an awkward position. This suggests that the Fed had lost effective control over short-term interest rates. The reason for the rise in interest rates has been widely debated. In my opinion,it was probably the combination of the following several factors that led to the funding crunch.

Paying Taxes

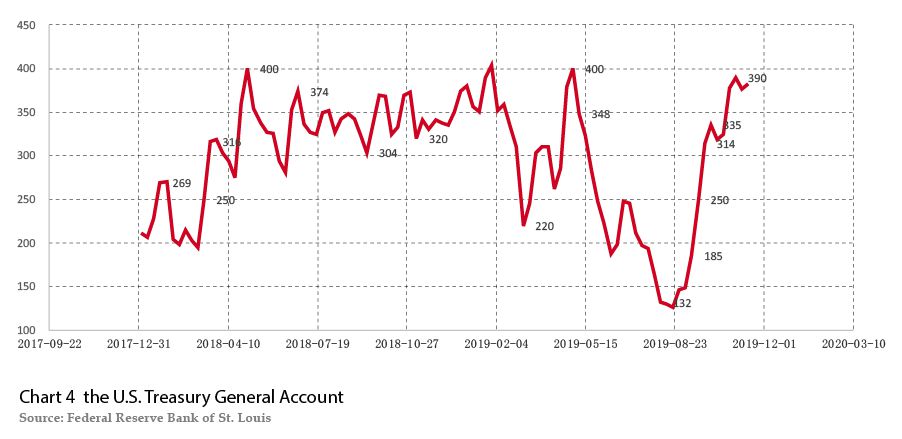

Firstly,companies pay taxes and the deadline for quarterly federal taxes was approaching. Money went into the Treasury General Account,or TGA – an account the Federal Reserve provides to the US Treasury which,similar to a checking account,allows Treasury to deposit or withdraw cash every day. (See Chart 4) This reduced the amount of reserves in the banking system.

Treasury Contributions

Secondly,for some time,Treasury sales had soared along with the growth in the US budget deficit. Net issuance reached US$1.3 trillion in 2018 and will hit US$1.2 trillion in 2019,double the amount of 2017. That would reduce the size of reserves in the banking system. When a large number of Treasury bonds are issued at about the same time,reserves in the banking system are withdrawn once investors make payments and