China's Corporate FX Flows: "FX Hoarding" or "Dishoarding"?

Although China has seen a large trade surplus in the past few years, it is striking that the large trade surplus has not been accompanied by large selling of foreign exchange (FX) on China's foreign exchange market. While this has prompted many market participants to talk about potential "FX hoarding," it has not resulted in a significant increase in official FX reserves or private sector FX deposits. In fact, private sector FX deposits dropped for the most of the past few years. Is this "FX hoarding" or "FX dishoarding"?

Our analysis below indicates that it is important to look holistically across the balance of payments (BOP), remittance, and conversion, as well as loans and deposits data, to formulate a comprehensive view of whether and how "FX hoarding" has evolved in the past few years. We find that corporates may have converted about US$0.3 trillion less than usual in the past few years, but these were mainly to repay FX loans instead of accumulating private sector FX deposits.

Below, we first take an overview to answer the question "Where did the trade surplus go", by linking up the different statistics and reconciliating their inter-relationships. Then we drill deeper into the remittance, conversion, as well as loans and deposits data, and construct some alternative metrics that can help to better measure the underlying corporate activities. Finally, we discuss some preliminary thinking about how any "FX dishoarding" may take place.

Where did the trade surplus go

Between April 22 (when USDCNY was at the previous low around 6.3) and March 25 of 2025, China customs reported US$2.8 trillion of trade surplus. But since the customs-reported trade surplus covers activities in various free trade zones in China, which do not necessarily incur cross-border fund movements, the metric more closely related to FX supply/demand was the BOP trade balance, which stood at US$2.2 trillion.

The difference of US$0.62 trillion is indeed very close to the customs-reported exports in these specially managed areas, which was US$0.75 trillion during the period. Furthermore, as China's services trade balance is negative during this period, the combined BOP trade and services surplus was smaller, at US$1.6 trillion over this period.

Against this trade and services surplus, about US$1.3 trillion was remitted into China, meaning a formation of US$0.3 trillion net foreign assets. These are not necessarily monetary assets – they could well be the formation of receivables or repayment of payables, etc. So far, the formation of these net foreign assets (less than 20% of the BOP trade and services surplus) looks rather reasonable.

Of the US$1.3 trillion remitted into China from the net goods and services balance, US$0.7 trillion was paid out for dividends and other distributions, and US$0.3 trillion represented net foreign direct investment (FDI). Notably, net FDI has turned slightly negative in recent years. Hence, net foreign remittance related to the real economy agents (such as corporates), encompassing the current account and FDI – was basically flat at less than US$0.3 trillion net inflow only.

There are three potential channels for these net inflows to move next: converting to RMB, remaining as private sector FX deposits, or repaying FX loans. FX conversions under current account and FDI were basically flat at about US$0.05 trillion over this period. FX loans were reduced by about US$0.4 trillion. Private sector FX deposits decreased by US$0.1 billion. The total is very close to the US$0.3 trillion inward remittance from the current account and FDI, suggesting that indeed the net inward remittances ended up in these three channels.

This comprehensive analysis more clearly illustrates why the cumulative US$2.8 trillion trade surplus over the recent three years did not significantly increase the official FX reserves or private sector FX deposits. It also shows that, to form a more comprehensive view of corporate FX activities, it is important to look at not only the trade and customs reports, but also a broader set of statistics from BOP, remittance data, conversion figures, and deposits/loans information.

From this analysis, we can also establish a conceptual framework to understand China's FX flows among the real economy agents (such as the corporate sector). Transactions recorded in the BOP give rise to cross-border fund remittance, and the net FX remittance ultimately flow into three avenues: being converted to RMB, used for repaying FX loans, and staying in FX deposits. Subsequently, we look at the remittance, the conversion, and FX loans and deposits in more detail.

Remittance

If the BOP could be seen as an "accrual accounting" representation of China's external transactions, the remittance could be seen as the "cash accounting" representation of these transactions. In a narrow sense, net inward FX remittances constitute the source of FX supply in China's FX market.

However, with the development of RMB cross-border settlement, a growing share of China's external transactions is now denominated in RMB. Hence, the BOP net flows and headline cross-border remittance data should be interpreted as a combination of FX-denominated and RMB-denominated flows. When studying FX supply and demand, particularly for recent years' data, it is important to make such a distinction and focus on the FX-denominated flows. Our estimate is that, since 2001, cumulative net FX remittances by banks' clients have amounted to US$3.8 trillion.

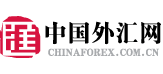

One important question in the market is how much is "unrepatriated”, among all the BOP basic balance (current account and FDI, i.e. those flows more closely related to the real economy agents such as corporates).This question arises because the cumulative BOP basic balance since 2001 amounts to well over US$5 trillion, but the remittance (with the inclusion of RMB) under current account and FDI is only about US$2.5 trillion. In other words, it appears that slightly more than half of the accumulated basic balance is "unrepatriated"(Figure 1).

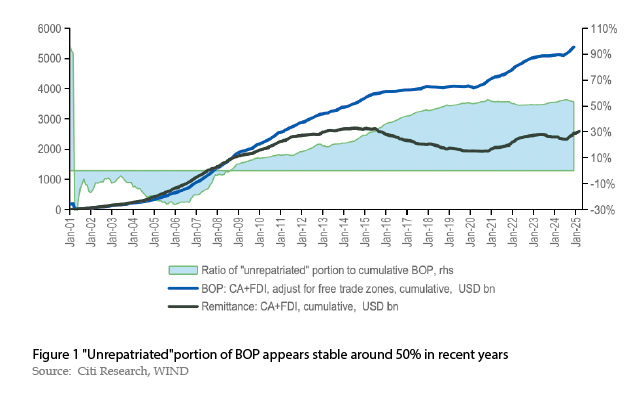

Terming this phenomenon as "unrepatriated" implies that many market participants consider it caused by exporters (who earn income) choosing not to repatriate these earnings to China. But a closer look at the ratio of import/export remittance vs. customs-reportedimport/export data shows that this is not the whole picture. For example, importers appear to consistently remit more than the headline imports reported by customs. Notably, this "over-remittance by importers"has been even more pronounced than the "under-remittance by exporters"over the past many years, even during periods of RMB appreciation (Figure 2).

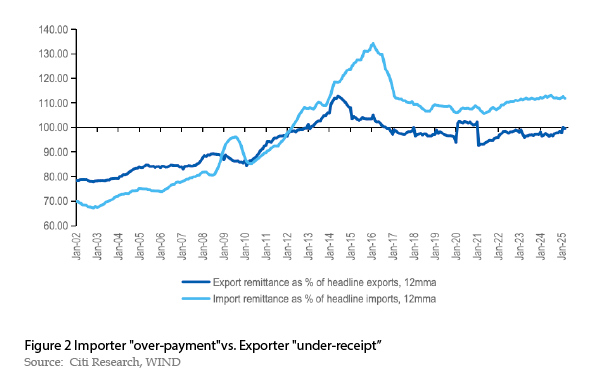

Potential measurement issues cannot be ruled out. As free trade zones were identified as one key factor behind the discrepancy between BOP and customs trade data, adjusting the remittance-to-trade ratio calculation by incorporatingfree trade zone data would eliminate most of the structural phenomenon of "under-receipt by exporters, over-payment by importers" (Figure 3). Although this adjustment is certainly oversimplified, it at least highlights the risks of overestimation in the "unrepatriated" phenomenon.

Another common perception is that the "unrepatriated" portion is held outside of China in monetary asset form, i.e. it can be turned into FX cash and repatriated to China easily by the Chinese corporates. This may not necessarily be the whole picture, either.

For example, a significant portion of these "unrepatriated" assets may be commercial receivables, which might not be entirely under Chinese corporates' management, unless these corporates first book their imports/exports transactions through an offshore affiliate (e.g. a trading company) in which case the affiliate interacts with the ultimate overseas vendor/customer. Additionally, these "unrepatriated" earnings could represent either an increase in assets or a reduction in liabilities. If liabilities (e.g. payables) were repaid, any "repatriation" would require reborrowing these liabilities – and that might not always be feasible or economical given the trading relationship or interest rate environment.

A third common question is whether policymakers could encourage more repatriation as a tool to boost FX supply. While more repatriation would certainly help improve FX supply on the margin, its effectiveness in influencing the exchange rate also depends on how much FX is converted to RMB. China has committed to current account convertibility since 1996, and the mandatory conversion requirement has long been removed. Indeed, for a long time, corporates have had the choice of holding "repatriated" funds as deposits, repaying FX loans, or converting them to RMB. If the policy objective is to boost FX supply and support the RMB exchange rate in the short term, reinstating mandatory conversion may undermine market confidence more than it provides benefits.

<